Chaplaincy in the Workplace

The phone rang and startled the chaplain awake from a deep sleep. She looked at the clock. 2:00 a.m., it read. An anxious voice on the other end said, “Chaplain, can you come now? There’s been an accident at the plant. We’ve lost someone.”

And so the marketplace chaplain went, donning her steel-toed shoes and grabbing her overcoat as she went out the door.

While this is not a common event, this kind of integration into the workplace is not unusual for a chaplain. Not unlike parish ministry, chaplains have the remarkable privilege of being with people in the best and the worst of times, as well as all the mundane moments in between. They are often present for life’s greatest joys as well as deepest pain.

Chaplaincy is a “sent” ministry. As an extension of the pastoral vocation, chaplaincy is a means of taking pastoral vocation into the world in various contexts: whether in the military, hospitals, hospice, or the corporate world. It is a very “in-the-world” kind of work as chaplains spend considerable time with people who might never step into a church building on their own and would certainly never seek the help of a pastor if they needed guidance.

What is a Marketplace Chaplain?

Unlike some other forms of chaplaincy that focus on acute care, ministering in the workplace emphasizes building ongoing relationships. This means that chaplains focus on a ministry of presence; not only during times of crisis but also during the regular work week.

Instead of sitting in a business office somewhere, marketplace chaplains are proactive in their work by going workstation to workstation, office to office, making their non-anxious presence known week by week. All of this is done without forcing conversations or being too quick with “Christianese.” Their regular presence cultivates a trust that is earned slowly through focused, non-judgmental listening. Chaplains lead with compassionate care.

People want to be treated as ends in themselves, not just as means to some other end or agenda.

They want to be seen. They want to be heard. They long to be understood. They need someone to hold out hope on their behalf.

Chaplains embody well the trajectory of the third core value of the Church of the Nazarene: Missional. The root word of missional means “sent.” We are not just a gathered people, but we are also a sent people. We join the Trinitarian, divine life of sending by going into the dark places. Chaplains carry with them the love of Christ into places the church might not be able to reach programmatically.

One of the primary tasks for chaplains, then, is to be hope-bearers in the world.

Chaplains carry hope when others cannot, especially in tragedy. It is fascinating how many people who identify as completely unbelieving will ask a chaplain for prayer. While they may not believe fully in the one who hears those prayers, they sense a kind of hope in knowing that they are being prayed for. Chaplains make manifest the hope of the sacred in those secular spaces. They help remind people that what they see is not all there is (2 Corinthians 4:18).

Bridging the Divide

Perhaps we have made too much of what we call the sacred-secular divide. I have heard it said that holy spaces are places where God will go, and unholy spaces are places where God won’t go. This is reflected in the rise of the word “Christian” being used as an adjective to describe things other than actual believers: music, works of fiction, schools, jewelry, clothing, and even nation-states.

But going into the dark places of the world has taught me that God is found even there—especially there, in fact.

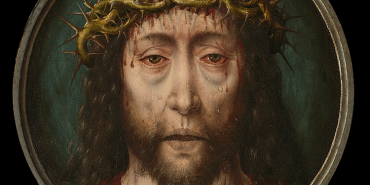

Isn’t it just like Jesus to be found in the places of deepest pain and in the darkest moments? In The Gospel of Mark, chapter 8, Peter the disciple is found trying to dissuade Jesus from going on one of the darkest journeys imaginable: the humiliating “defeat” of death on a cross. Jesus rebukes him for thinking human thoughts and not godly ones. It was absurd for Peter to believe that a holy God would willingly be subjected to torture and death. The cross was a dismal place after all, and not fit for a king – at least not in Peter’s mind. Peter was going to try to talk Jesus out of it.

But Jesus took that instrument of death and made it holy. The most profane were transformed and turned into salvation for the world.

Immediately following this transaction with Peter in Mark 8:34, Jesus turns to the crowd to say, “All who want to come after me must say no to themselves, take up their cross, and follow me.” So, as followers of Jesus, we too must enter into the self-emptying way (Philippians 2).

This means that we must follow Jesus into the unholy places that are made holy by the presence of God. Instead of retreating into silos, wringing holy hands over the state of the world and hoping people will come to us, we — like the chaplain — are called deeper into the pain and darkness.

It also means that we, following the example of chaplains, must do the hard work of holding open space for others. Only a non-judgmental space acknowledges the image of God already present in those we interact with, believing as Wesleyans do that God is already at work.

As we enter the dark places of the world bearing Christ’s name, there is a good chance we’ll find God waiting there.

Rich Shockey is an ordained elder in the Church of the Nazarene and director of chaplain services for Marketplace Chaplains.

Holiness Today, January/February 2018

Please note: This article was originally published in 2018. All facts, figures, and titles were accurate to the best of our knowledge at that time but may have since changed.